Moving to Switzerland in 2025: Your Essential Handbook for Swiss Residency, Taxes, and Financial Planning

Moving to Switzerland is an exciting adventure—but navigating Swiss residency permits, taxes, deductions, and financial planning can feel overwhelming. This comprehensive 2025 guide breaks down everything you need to know, from obtaining the right residency permit (L, B, C, and more) to understanding tax residency rules, filing your Swiss tax return and implementing effective tax optimization strategies. Whether you’re an EU/EFTA citizen or coming from outside Europe, planning a short-term stay or a permanent relocation, this guide will provide the clarity and depth you need to smoothly manage your residency status and financial obligations.

Swiss Residency Permits Overview

Switzerland requires all foreign nationals staying more than three months to obtain a residence permit. There are several types of permits, each with its own conditions and duration. The main categories include:

- L Permit – Short-Stay Permit: For short-term residence up to one year (often linked to short work contracts or extended stays)

- B Permit – Residence Permit: For longer-term temporary residence (annual or multi-year, renewable, commonly issued for workers and residents)

- C Permit – Settlement Permit: For permanent residence after fulfilling certain years of stay and integration criteria

Other special permits exist (e.g., Ci permit for family members of diplomats, G permit for cross-border commuters, F for provisionally admitted foreigners, N for asylum seekers, S for persons needing protection), but the L, B, and C permits are the most relevant for typical expats and foreign employees.

Below, we review each main permit type in a chronological order, from initial short stays to long-term settlement, and explain how one can transition through them.

Short-Term Residence (L Permit) – Up to 12 Months

What is an L Permit?

The L Permit is a short-term residence permit for stays in Switzerland up to one year. It is often used for people on temporary assignments, internships, or job contracts shorter than a year. This permit can sometimes be extended for a second year, but generally has a maximum duration of 24 months.

The L permit is usually tied to a specific purpose (such as a particular job or study program) and may come with restrictions – for example, non-EU holders of an L permit might be limited in changing employers or cantons (Swiss states).

Who can get an L Permit?

EU/EFTA Citizens

Under the Agreement on Free Movement of Persons, EU/EFTA nationals have a more straightforward process and may obtain an L permit for temporary stays, such as looking for work (often valid 3–6 months, extendable to a year if job prospects continue) or for a short-term job. They generally do not need an entry visa for Switzerland, but if staying over 90 days, registration for a permit is required.

Non-EU (Third-Country) Citizens

Non-EU nationals usually need an L permit for short stays beyond 90 days, but obtaining it is more complex. It typically requires a work contract or specific reason and is subject to quotas.

Swiss employers must sponsor the permit and prove that no suitable Swiss/EU candidate was available for the job. The process often starts with the employer applying to cantonal authorities, followed by federal approval through the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM).

Non-EU nationals also generally need a valid entry visa (Schengen visa) if coming for work or long stays, which is issued only after the permit approval.

Key features of the L Permit

- Valid for up to 12 months; can be extended up to a total of 24 months in some cases

- Often tied to the duration of an employment contract or specific activity

- For non-EU holders, changing jobs or cantons may require special permission

- The L permit is intended for temporary stays and does not lead directly to permanent residency

- Many individuals on an L permit who continue their stay transition to a B permit once they secure longer-term employment or meet other criteria

- Switzerland imposes annual quotas for L permits issued to third-country nationals, subject to availability each year

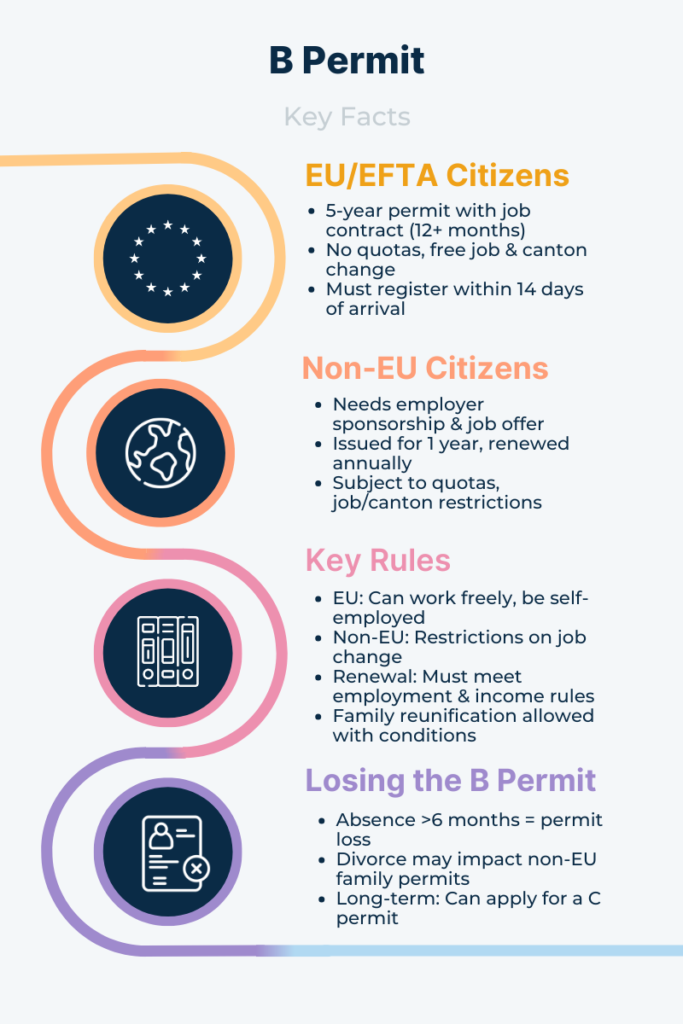

Long-Term Residence (B Permit) – Renewable Residency

What is a B Permit?

The B Permit is the standard residence permit for longer-term stays in Switzerland. It allows foreign nationals to live and work in Switzerland for an extended period, subject to renewal. Initially, a B permit is often issued for one year (especially for non-EU citizens) or for five years (for many EU/EFTA citizens with stable employment or sufficient finances).

The B permit is renewable as long as the conditions (such as employment or financial means) are met, and it serves as a bridge toward permanent settlement (C permit) after several years.

B Permit for EU/EFTA Citizens

EU/EFTA nationals benefit from Switzerland’s agreements with the EU on freedom of movement, making it relatively easier to get a B permit.

If an EU/EFTA citizen has a work contract of at least 12 months (or is permanent/open-ended), they are typically granted a B permit valid for 5 years. This permit is automatically renewed for another five-year period as long as the person remains employed or financially self-sufficient.

If an EU national becomes involuntarily unemployed for longer than 12 consecutive months, the renewal might be limited to a shorter duration (e.g., a one-year B permit).

EU/EFTA nationals do not face quotas, and they have the flexibility to change jobs and move between cantons freely under the B permit. They also do not need a prior visa to enter Switzerland; they must, however, register with local authorities and apply for the permit within 14 days of arrival.

B Permit for Non-EU (Third-Country) Citizens

For non-EU nationals, obtaining a B permit usually requires: a Swiss job offer and employer sponsorship, proof that the employer could not find a suitable Swiss/EU candidate for the role, and meeting qualification and salary criteria set by authorities.

B permits for non-EU citizens are typically issued for 1 year at a time and must be renewed annually.

They are also subject to yearly quotas. Non-EU B permit holders are usually tied to the canton and sometimes the employer that secured the permit; a change of job or canton might require a new approval.

Rights and Conditions of a B Permit

Work and Self-Employment

B permit holders can work for the employer who sponsored them.

EU/EFTA B permit holders can generally take any job or even become self-employed without prior authorization.

Non-EU B permit holders may need additional permission to change employers or to switch to self-employment, particularly if their permit was granted for a specific job or under certain conditions.

Duration and Renewal

The permit must be renewed on its expiry (annually for non-EU, or every 5 years for EU in normal cases). Renewal requires showing that you still meet the conditions (ongoing employment, sufficient income, no heavy reliance on social welfare, etc.). Be mindful of renewal deadlines – generally you should apply to renew about 2–3 months before expiration.

Family Reunification

B permit holders can usually bring immediate family (spouse and children under 18) under family reunification rules. The sponsor must have sufficient housing and income to support dependents.

EU/EFTA citizens have broad rights to reunite family. Non-EU citizens with B permits can also apply to bring family, but must meet integration criteria (e.g. the family might need to show basic local language knowledge) and other conditions as per the Foreign Nationals and Integration Act. For example, spouses of non-EU B permit holders must often demonstrate at least A1 level in a national language or enrollment in a language course.

Geographic Mobility

B permits are tied to a canton at issuance.

EU/EFTA nationals can move to a new canton with minimal formalities (just registering new address), thanks to freedom of movement.

Non-EU nationals usually must request permission to change cantons while on a B permit. In practice, if the job is in another canton, that canton must agree to take over the permit.

Losing a B Permit

If you leave Switzerland long-term or no longer meet conditions, your B permit can expire or be revoked. For instance, spending more than 6 months abroad without permission can cause loss of a B permit. If a B permit holder on family reunification divorces the sponsoring spouse within the first few years, the permit might not be extended unless certain integration conditions are met.

In summary, the B permit is the mainstay for foreigners looking to live and work in Switzerland for more than a year. It grants a stable status but is time-limited and contingent on meeting requirements. After 5–10 years on a B permit, many residents become eligible to apply for the permanent C permit.

Permanent Settlement (C Permit) – Permanent Residency

What is a C Permit?

The C Permit is a settlement permit that grants permanent residency in Switzerland. Holders of a C permit have an open-ended right to live and work in Switzerland, with no more periodic renewals needed (the permit card itself is typically renewed every 5 years for document purposes, but the status does not expire if conditions are maintained).

A C permit allows you to reside in Switzerland indefinitely, change jobs or cantons freely, and essentially puts you on near-equal footing with Swiss citizens in many areas of daily life (except political rights and a few restrictions). For example, C permit holders can work anywhere without authorization, become self-employed easily, and purchase real estate without the special permits that non-residents or B permit holders might need. Obtaining a C permit is a key milestone for expats, and it is also a prerequisite for applying for Swiss citizenship in the future.

When can you get a C Permit?

The timeline for a C permit depends on your nationality and how well integrated you are.

Standard Rule – 10 Years

In general, foreign nationals become eligible for a C permit after 10 years of continuous residence in Switzerland on temporary permits (such as B). This is the standard requirement under Swiss law for most third-country (non-EU) citizens.

Fast Track – 5 Years

Certain nationalities and groups can get a C permit after only 5 years of uninterrupted residency. This applies to EU/EFTA citizens from countries with a reciprocal settlement treaty, as well as a few other countries like the United States and Canada which have agreements with Switzerland.

Citizens of EU-15 states (like Germany, France, Italy, etc.) and EFTA states (Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein) are usually granted a C permit after 5 years of living in Switzerland regularly.

Nationals of other EU countries (primarily newer EU member states) traditionally waited 10 years, although in practice many can also get C in 5 years if they meet integration criteria.

US and Canadian citizens are notable non-EU nationals who are allowed to apply for C permits after 5 years of residence, thanks to long-standing agreements.

Family Members

Spouses of Swiss citizens or of C permit holders may be able to receive a C permit after 5 years of residence (instead of 10), as long as they are well integrated, per Swiss regulations.

Children who grow up in Switzerland often can get C when the parents do, or sometimes even sooner if they meet conditions.

Integration and Language Requirements

Since the Foreign Nationals and Integration Act (FNIA) came into force in 2019, Switzerland explicitly conditions the granting of C permits on integration benchmarks. Even if you have resided for the required period, you must generally:

- Obey the law and constitutional values

- Have no record of dependence on social assistance

- Participate in economic life (working or studying)

- Demonstrate language proficiency in the local official language

For most applicants, this means showing at least A2 level speaking and A1 writing skills (basic proficiency) in the language of your canton for a standard C permit.

For an early C permit after 5 years (instead of 10), the bar is higher – typically B1 level oral and A1 written is expected, except for nationals of countries with a settlement treaty (who might be exempt from the higher language level).

In practice, cantons may require language certificates (e.g., German, French, or Italian exams) when you apply for C. Integration criteria also include being employed or otherwise financially self-sufficient and showing you are socially and culturally integrated (e.g., no criminal record, respect for Swiss laws).

Benefits of a C Permit

Stability

The C permit has no expiration as long as you remain a resident of Switzerland. (You can leave Switzerland for up to 6 months without losing it, or even longer in special approved cases.)

Employment Freedom

You can take any job or start a business without needing permission. You are no longer subject to foreign-worker quotas or labor market tests.

Geographic Mobility

Free to live in any canton. Cantonal permissions that applied under a B permit no longer restrict you.

Family Reunification

As a C permit holder, you continue to have the right to reunite immediate family members (spouse, children), similar to citizens.

No Longer Taxes at Source

One significant change is in taxation – with a C permit, you are typically no longer taxed at source on your Swiss employment income. Instead, like Swiss citizens, you will file an annual tax return and pay taxes by assessment (more on this in the tax section).

Pathway to Citizenship

Holding a C permit is a requirement for applying for ordinary naturalization (citizenship). You must have a C permit and at least 10 years of total residency (with some exceptions for early citizenship in certain cases). In fact, 10 years is both the usual time for C permit eligibility (for those who didn’t get it in 5) and the minimum residence for citizenship application. Many expats choose to remain on a C permit long-term without becoming citizens, as it grants nearly all rights except voting.

Obtaining a C permit marks the achievement of permanent resident status in Switzerland. At this stage, your interaction with immigration authorities becomes minimal compared to the yearly renewals of a B permit. The focus often shifts to long-term considerations like integration into the community and, if desired, working toward Swiss citizenship.

Swiss Tax Residency Rules and Obligations

Switzerland’s tax system distinguishes between tax residents and non-residents. Simply having a residence permit (like a B or C) does not automatically make you a tax resident in every scenario – it depends on your physical presence and intent.

In practice, most people living in Switzerland on a permit will be considered tax resident from the time they settle here. Understanding the tax residency rules is crucial because Swiss tax residents are taxed on their worldwide income and assets, whereas non-residents are taxed only on Swiss-source income in specific cases.

When Do You Become a Swiss Tax Resident?

Under Swiss law, an individual is deemed a tax resident (subject to unlimited tax liability) if any of the following conditions are met:

- You establish a domicile in Switzerland when you settle physically and intend to stay permanently, typically coinciding with registration at your local municipality*

- You stay in Switzerland for a certain duration that exceeds a minimal threshold:

- 30 days or more, with engagement in a gainful activity (working)

- 90 days or more, without any gainful activity (e.g., retired persons or long visits)

*Establishing domicile means your personal center of vital interests—such as family, housing, and economic ties—shifts to Switzerland, usually requiring a minimum stay of 30 days if employed.

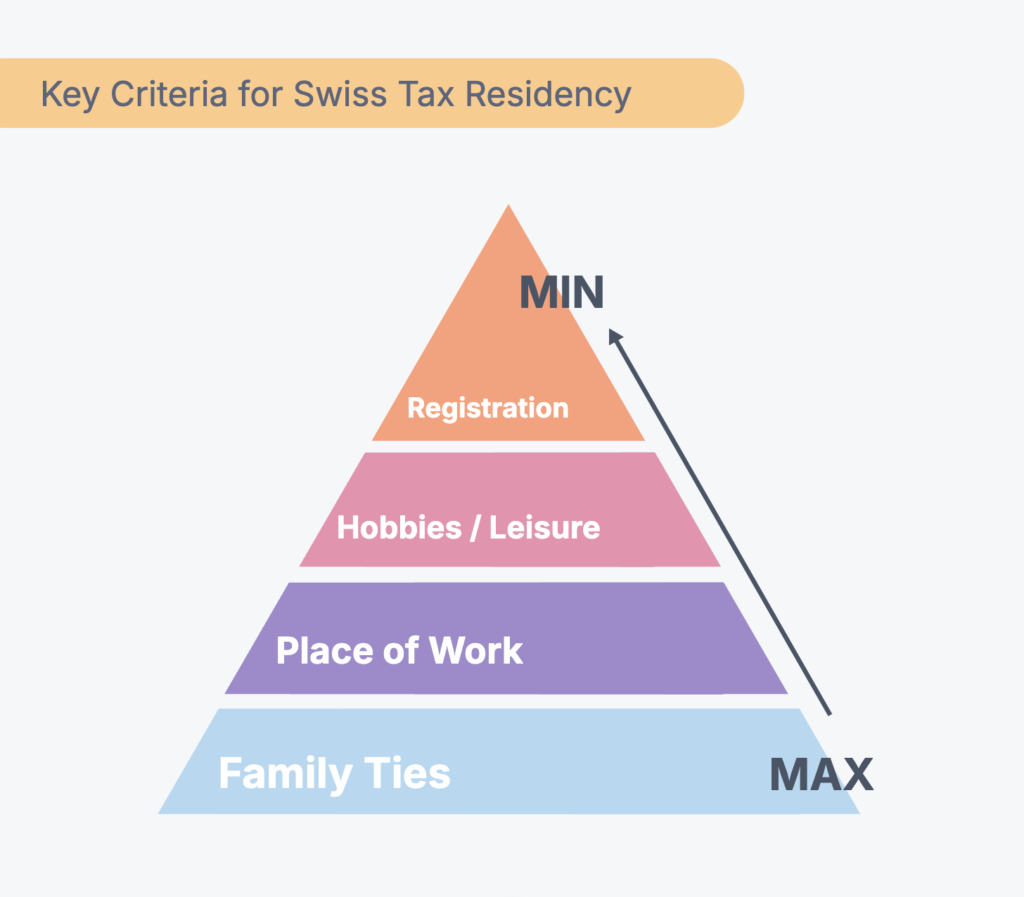

Tax Residency Determination: Factors Ranked by Importance

When an individual could be seen as a resident in more than one country, Swiss tax authorities determine which location is the “main tax residence” by examining several factors. Although physical presence is crucial—particularly the 30-day or 90-day rule for new arrivals—other considerations also come into play.

These factors illustrate why, in certain cross-border (international) scenarios, connections such as family and place of work carry significantly more weight in determining tax residency than official registration.

Family Ties (Most Important)

This is the most significant factor in determining Swiss tax residency. If a person’s immediate family (such as spouse and children) resides in Switzerland, it strongly indicates tax residency.

Place of Work

The second most important factor. If an individual works in Switzerland, it suggests a strong connection to the country and influences tax residency status.

Hobbies / Leisure

This factor carries less weight but is still considered. If someone frequently engages in leisure activities in Switzerland, such as sports or cultural events, it may contribute to tax residency assessment.

Registration (Least Important)

Official registration in Switzerland (such as holding a residence permit) is the least important factor. While it is relevant, it does not outweigh the presence of family or place of work in determining tax residency.

In simpler terms, if you move to Switzerland to live and work, from day one of your employment here you are considered a tax resident (since you’ll surpass 30 days with work). If you move without working (say, a retiree or student), after 90 days of presence you become tax resident. In fact, Swiss law’s thresholds (30/90 days) are shorter than the more commonly known “183-day rule” used in many other countries. So you can become a Swiss tax resident in as little as one to three months of being here.

Importantly, tax residency usually starts from the date you actually move to Switzerland with the intent to stay. If you arrive mid-year, you will be considered a Swiss tax resident for the portion of the year from your arrival. Swiss authorities will often pro-rate your income for the first year to determine an annualized rate for progressive taxes. For example, if you moved on July 1 and earned CHF 50,000 in Switzerland in the second half of the year, they might calculate as if you’d earn CHF 100,000 in a full year to apply the tax rate, then tax you on the CHF 50k actually earned.

Tax Residency vs. Other Types of Legal or Economic Presence

Tax Residency vs. Citizenship

In Switzerland, nationality* plays only a secondary role in taxation. As a rule, your tax situation is determined by where you live and work rather than by your citizenship.

More important than your nationality is which residence permit you hold (B or C).

This permit determines whether your salary will be taxed at source or whether you must file an ordinary tax return each year.

* US citizens remain subject to US tax law even if they have unlimited tax liability in Switzerland.

Tax Residency vs. Domicile

When deciding a taxpayer’s official domicile for tax purposes, Swiss authorities look at whether you intend to remain in Switzerland long term.

In most cases, if you live in Switzerland with the intention of staying, you establish a tax domicile.

If, by contrast, you only maintain a place to stay—like a holiday property or hotel—without any plan to remain permanently, you do not create a full tax domicile. Instead, you typically owe only those taxes associated with the property itself, such as property tax, pro rata wealth tax, or visitor’s fees.

Tax Residency vs. Ordinary Residency

In the vast majority of situations, your ordinary residence in Switzerland also establishes your main tax domicile. There are, however, exceptions. For example, if your employer sends you to work in another country on a temporary assignment, but your family remains in Switzerland, you might still be considered a tax resident in Switzerland.

Tax Residency vs. Permanent Establishment

A permanent establishment (PE) is a fixed location—such as an office, branch, or factory—through which a company carries out economic activities. Having a PE typically triggers tax obligations in the country where it is located.

While permanent establishments commonly arise for corporate structures or self-employed individuals, it is worth noting that even employment can create a PE if an employee’s presence at a particular location is substantial enough to represent the company’s operations. This can be especially relevant for employees working long-term from a home office or satellite site in Switzerland. If that work constitutes a significant business activity (e.g., contract negotiations, key decision-making, or continuous client management), authorities may deem it a PE, leading to tax implications.

Taxation of Residents: Worldwide Income and Wealth

Once you are a Swiss tax resident, you are subject to taxation on your worldwide income and net wealth. Switzerland taxes personal income at federal, cantonal, and municipal levels, and also levies an annual wealth tax on net assets (at cantonal level) for residents. This means your salary, self-employment earnings, investment income, etc., from both Swiss and foreign sources are generally reportable. (Foreign real estate and certain foreign business income are typically exempt from Swiss tax per se but still considered for rate progression, depending on cantonal rules).

As a resident, you will file an annual Swiss tax return declaring your global income and assets, unless you are a short-term resident under a special regime (see Withholding Tax section below). Switzerland has relatively moderate income tax rates by Western European standards (with significant differences by canton), and some cantons have low wealth taxes. There are also special expatriate deductions and, for the very wealthy who qualify, a lump-sum taxation regime based on expenditure rather than income.

Wealth Tax

One unique aspect is that Swiss residents must declare worldwide assets such as bank accounts, investments, and real estate for wealth tax. The tax rates on wealth are progressive but low (often well below 1% annually) and typically include exemptions for a basic amount of assets. Still, if you become a Swiss resident, be prepared for this aspect of taxation, which might be new if you come from a country without a wealth tax. For a deeper dive into how wealth tax works and ways to plan accordingly, check out our dedicated blog post on Swiss Wealth Tax.

Federal Income Tax Changes (2025 Update)

Starting January 1, 2025, Switzerland introduced a reduction in federal income tax rates across all income brackets, following a recent referendum. The reduction ranges from approximately 5% to 11%, depending on your income level. Specifically, federal income tax rates now start from 0% on incomes below CHF 18,500, rising progressively to a maximum of 11.5% on income above CHF 793,000, with the exact rate slightly lower at each bracket compared to previous years. This update will modestly reduce the federal tax liability for most residents from 2025 onward, potentially generating savings of a few hundred to several thousand francs per year, particularly benefiting higher earners.

Taxation of Non-Residents: Swiss-Source Income

If you are not a tax resident of Switzerland, you generally only owe Swiss taxes on certain income or assets that have a strong connection to Switzerland (this is called limited or source-based tax liability).

Non-resident individuals are taxed on Swiss sources such as:

- Swiss employment income – e.g. salary for work performed in Switzerland (even short term)

- Directors’ fees – remuneration for serving as a board member of a Swiss company

- Swiss investment income – dividends from Swiss companies, interest on Swiss bank accounts (note: Swiss bank interest for non-residents is often tax-exempt, but withholding tax may apply to dividends)

- Swiss real estate – ownership of property in Switzerland triggers Swiss tax on rental income or imputed rent, and property tax/wealth tax on the real estate

- Swiss pensions – payments from Swiss pension schemes or social security

- Business income from a Swiss permanent establishment – if you’re a business owner with a fixed place of business in Switzerland

These Swiss-source incomes might be subject to withholding taxes or filing requirements in Switzerland even if you live abroad. For example, if you live in Germany but work in Basel as a cross-border commuter (with a G permit), Switzerland will tax your Basel salary at source, typically at a preferential rate due to bilateral agreements. Double taxation treaties (discussed below) further determine what Switzerland can tax for non-residents. The key point is: non-residents don’t pay Swiss tax on foreign income, only on specific Swiss income.

Withholding Tax (Quellensteuer) for New Residents

When you first move to Switzerland and start earning, you may encounter the withholding tax system (called Quellensteuer in German). This is a system where taxes are directly deducted from your salary each month by your employer, instead of you paying taxes via an annual tax bill. Withholding tax applies to foreign workers who are not yet permanent residents or citizens. In practice, if you hold a B permit or L permit (or are a foreign employee without a C permit), your Swiss employer will withhold income tax from your paycheck and remit it to the authorities on your behalf.

The rates are determined by cantonal tax tables, taking into account an average of federal, cantonal and municipal taxes and your personal situation (marital status, number of children, etc.).

For many foreigners, this withholding tax simplifies things – initially, you do not have to file a tax return if your only income is Swiss salary. The withheld tax is your final tax in that case.

However, there are important exceptions and thresholds to know:

- If your gross employment income exceeds CHF 120,000 in a calendar year (equivalent to CHF 10,000 per month), you must file an ordinary tax return—even if you hold a B permit

In other words, once you earn above this threshold, Switzerland will switch you to the standard tax filing system (called subsequent ordinary assessment). The taxes withheld from your salary will be credited against your final tax bill, and you may have to pay additional tax or get a refund depending on your total income and deductions.

Secondary Triggers for Mandatory Ordinary Tax Filing in Switzerland

Individuals who are taxed at source (Quellensteuer) generally only file an ordinary tax return if their annual employment income exceeds CHF 120,000. However, there are several secondary triggers besides this CHF 120k threshold that can obligate a person to file a standard tax return.

In particular, taxpayers paying Quellensteuer must proactively file a return if they have certain other income sources or assets not covered by withholding tax. Failing to report these can lead to penalties, since tax authorities may not automatically be aware of such income or wealth.

Below is an overview of the key secondary triggers that can require an ordinary tax filing, along with typical thresholds and examples.

Additional Income Not Subject to Withholding Tax

Having significant non-wage income that isn’t already taxed at source will trigger the need for an ordinary tax return. This includes income like investment earnings (interest or dividends), rental income, alimony, self-employment or freelance earnings, pension or social security benefits, lottery winnings, or other taxable compensation outside of your regular salary.

Swiss tax law was revised in 2021 to give each canton the authority to set its own threshold for what amount of such extra income is considered “significant”. In practice, the thresholds vary widely by canton – some are very low, while others use a case-by-case assessment with no fixed limit.

Significant Assets or Property Ownership

Owning substantial assets or property can also mandate an ordinary tax filing. This is because Switzerland levies cantonal wealth taxes and taxes on property (including the imputed rental value of owner-occupied real estate) that are not captured by payroll withholding. If an individual subject to withholding tax has “significant taxable wealth,” they are required to file a return so that their income and net worth can be assessed together. Each canton defines “significant” wealth quite differently as well: some set specific wealth thresholds (often in terms of total net assets) and sometimes differentiate by marital status.

Cantonal Thresholds for Non-Withheld Income and Wealth

| Canton | Additional Income Not Subject to Withholding Tax | Assets (Single) | Assets (Married) |

| Aargau | From CHF 10,000 | From CHF 100,000 | From CHF 100,000 |

| Basel Stadt | From CHF 500 | From CHF 75,000 | From CHF 150,000 |

| Bern | From CHF 3,000 | From CHF 150,000 | From CHF 150,000 |

| Geneva | No known threshold | No known threshold | No known threshold |

| Lucerne | Interest income: CHF 2,000; Self-employment earnings / Alimony: CHF 5,000 | From CHF 62,500 | From CHF 125,000 |

| St. Gallen | No threshold / Case-by-case assessment | From CHF 75,000 plus CHF 20,000 for each underage child | From CHF 150,000 plus CHF 20,000 for each underage child |

| Ticino | From CHF 3,000 | From CHF 50,000 | From CHF 50,000 |

| Wallis | No known threshold | No known threshold | No known threshold |

| Zug | From CHF 2,000 | From CHF 100,000 | From CHF 100,000 |

| Zurich | From CHF 3,000 | From CHF 80,000 | From CHF 160,000 |

Key Factors Influencing Tax Liability Under Retroactive Filing

To ensure consistency across multiple tax scenarios, we use a standardized taxpayer profile in all following examples. This allows us to isolate and showcase the impact of different tax-related factors while keeping key personal and financial variables unchanged. The subject in this example has the following characteristics:

💰 Annual Salary: CHF 108,000

🏦 Wealth: CHF 70,000

💍 Marital Status: ❌ (Single)

👶 Children: ❌ (None)

📍 Residence: 🇨🇭 Zürich-City (ZH) or Rüschlikon (ZH)

Impact of Residency

While the withholding tax at the cantonal level remains the same, retroactive filing can significantly affect an individual’s tax liability. This graphic compares two taxpayers—one residing in Zürich-City, a high-tax municipality, and the other in Rüschlikon, a relatively low-tax municipality—highlighting the impact of location. After retroactive filing, the taxpayer in Zürich faces a higher tax burden, whereas the one in Rüschlikon benefits from a reduced liability. This underscores how residency within the same canton can lead to different tax outcomes.

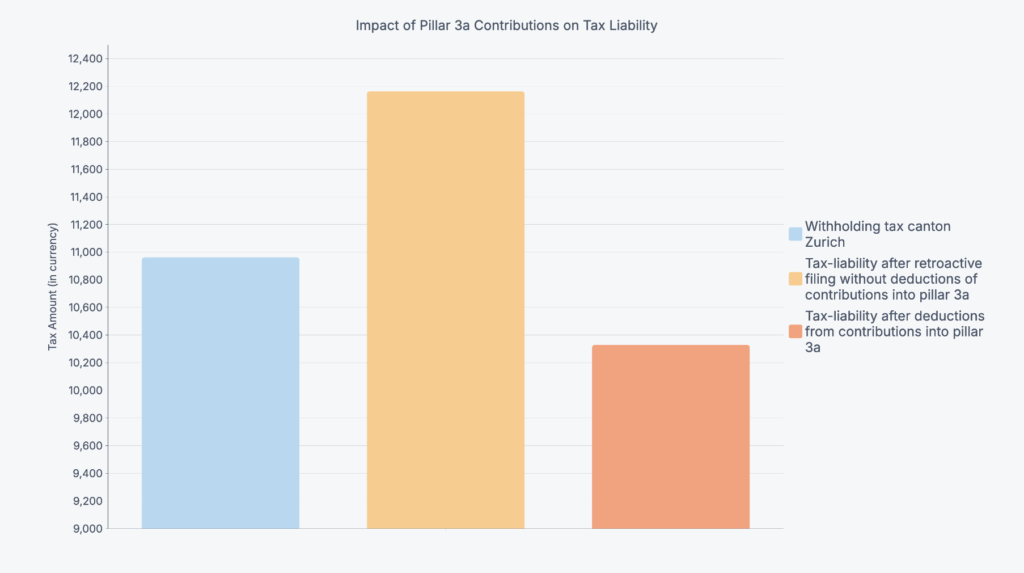

Impact of Pillar 3a Contributions

In Switzerland, the maximum allowable contribution to Pillar 3a is CHF 7,056, and this example assumes that the individual has chosen to contribute the full amount. Under the withholding tax system, Pillar 3a contributions are not deductible, meaning taxpayers subject to withholding tax cannot benefit from this reduction. However, by applying for retroactive filing, the CHF 7,056 contribution can be deducted from taxable income, leading to a lower tax burden.

Impact of a 13th Month Salary

The individual in this scenario still has an annual salary of CHF 108,000 but receives an additional 13th month salary in November, which increases their withholding tax due to the progressive tax rate structure. Under the withholding tax system, extra income—such as a bonus or a 13th month salary—is taxed at a higher rate than regular monthly earnings because it temporarily pushes the total taxable income of that month into a higher tax bracket, where a greater rate applies. As a result, this additional payment can lead to a disproportionately higher tax burden for that month, potentially reducing the overall financial benefit of receiving it.

Be Aware of Potential Downsides

Once you opt for a retroactive assessment, some cantons require you to remain in the ordinary tax filing system for subsequent years—even if your deductible expenses decrease or disappear. This can sometimes result in a higher tax bill than if you had continued with the standard withholding system.

Tax Return Filing Deadlines and Extensions

In Switzerland, your annual tax return is typically due by March 31 of the following year for most cantons and federal taxes, covering income earned in the preceding calendar year (January 1 – December 31). However, deadlines can vary slightly by canton. For example, the canton of Vaud has an earlier initial deadline around mid-March (with an automatic grace period), while others, such as Geneva, set their deadlines at March 31 with extensions available upon request. Extensions are usually straightforward to obtain, often until June or September, though some cantons may charge a nominal fee (e.g., CHF 20–60 in Geneva).

For more detailed and up-to-date information on cantonal deadlines and how to request an extension, refer to our recent updated blog post on Swiss Tax Filing Deadlines.

Tax Deductions and Allowances Overview

Child and Childcare Deductions

Starting in 2025, the federal deduction per child increases from CHF 6,600 to CHF 6,800. Additionally, you can claim childcare expenses up to CHF 10,400 annually at the federal level.

Insurance Premium Deductions

Switzerland permits limited deductions for certain mandatory insurance premiums. However, these deductions are modest and usually capped.

For more detail on specific limits and conditions, see our blog post on How to Manage Healthcare Costs.

Property Deductions and Imputed Rental Value

Homeowners in Switzerland can deduct actual property maintenance expenses or opt for a cantonal flat-rate deduction. However, homeowners must also declare a theoretical rental income known as Eigenmietwert, which is taxable as income, though partially offset by deductions for mortgage interest and maintenance.

Charitable Donations

Donations made to registered charities or recognized NGOs can be deducted from your taxable income, typically up to around 20% of your annual income.

Educational Expenses

For 2025, the federal deduction for eligible educational and training expenses is set at CHF 13,000. This deduction applies to costs related to professional development or career-oriented education.

Alimony Payments

If you pay alimony or maintenance to a former spouse or child, these payments are deductible from your taxable income.

Social Security Contributions and Their Tax Impact

In Switzerland, employees and employers share mandatory contributions toward social security schemes, including old-age and survivors’ insurance (AHV), disability insurance (IV), and unemployment insurance (ALV). Typically, these social security deductions amount to approximately 5–6% of your gross salary, with your employer matching your contribution. Although deducted automatically from your paycheck, these contributions significantly impact your taxable income, as they are fully tax-deductible. Your annual salary certificate (Lohnausweis) generally shows your income net of these mandatory deductions, effectively reducing your taxable income.

Additionally, voluntary contributions, such as extra payments into your occupational pension (Pillar 2) to compensate for previous gaps, are also tax-deductible. Such voluntary buy-ins can be an effective tax planning strategy, especially in higher-income years. Furthermore, contributions to private pension savings accounts (Pillar 3a) offer another tax-saving opportunity, with contributions fully deductible from taxable income.

Change in Status (C Permit or Marriage)

If you obtain a C permit, or if you marry a Swiss citizen or C permit holder while on a B permit, your tax situation changes. C permit holders (and Swiss citizens) are not subject to automatic wage withholding; instead, they file tax returns and pay tax bills in installments. When a B-permit holder is married to a Swiss or C permit spouse, the couple must file a joint tax return, which means the B permit holder is taken off withholding tax and moved to ordinary taxation (because the spouse is taxed ordinarily).

In the year your status changes (e.g., you receive your C permit mid-year), the withholding stops and you’ll be asked to file a return for that year so that the entire year is taxed under ordinary rules.

In summary, the withholding tax system is a way to simplify tax collection for most foreign workers in their initial years. But it is essentially a prepayment. The ultimate tax obligation is determined either at source or via a return, depending on your income level and personal situation.

Avoiding Dual Tax Residency and Double Taxation

When moving internationally, there’s a risk of being considered a tax resident by two countries at the same time, which can lead to double taxation (being taxed on the same income twice). Switzerland, like many countries, has a network of double taxation treaties (DTTs) to prevent this. If you leave your home country to move to Switzerland, you should coordinate your tax residency carefully.

End Tax Residency in Former Country

Make sure to follow the proper steps to cease tax residency in the country you’re leaving (for example, deregistering, ceasing to have a permanent home there, etc.). Many countries use a 183-day rule or close of the tax year to determine residency, so timing your move around year-end or clearly documenting your departure can help avoid being deemed resident for overlapping periods.

Start Tax Residency in Switzerland

Register promptly in Switzerland and know the date you became resident here for tax purposes. As noted, this could be the arrival date if you intend to stay and work. Swiss authorities will consider the “totality of circumstances” – that your move date, rental lease start, employment start, etc., all line up to indicate you shifted your life to Switzerland. Ensure this date aligns with when you end tax residency in the other country, to the extent possible.

Resolving Dual-Residency Conflicts

If both countries’ domestic laws claim you as a resident (it can happen, e.g., you spent 5 months in one country and 7 in the other in the same year), the double tax treaty between Switzerland and that country will have tie-breaker provisions. These usually consider where you have a permanent home, where your center of vital interests is (family and economic ties), where you habitually reside, and your nationality, in that order, to assign one country as your primary residence for tax purposes.

Double Tax Relief

Even when you’re only a Swiss tax resident, you might still have foreign income (like rental income from a property abroad) that gets taxed in that foreign country. Switzerland provides relief either by exemption or tax credits as arranged in treaties, so you don’t pay tax twice. The tax regulations and treaties ensure that income is taxed once or that credit is given for foreign tax paid. For example, Swiss tax law will reserve the application of treaty provisions – meaning the treaty can override domestic rules to eliminate double taxation.

Tax Optimization Strategies

Pillar 3a Maximization

Contributing to a Pillar 3a retirement savings account is one of the most effective ways to reduce your taxable income in Switzerland. In 2025, employed individuals covered by a company pension scheme can deduct contributions of up to CHF 7,258 from their taxable income. Self-employed individuals without occupational pensions can contribute up to 20% of their net earnings, capped at CHF 36,288 in 2025. This should offer significant tax savings while simultaneously building retirement savings.

Timing of Income and Deductions

Carefully timing your income and deductible expenses can significantly impact your taxes. If possible, consider deferring additional taxable income—like bonus payments, certain pension withdrawals, or bond interest—to a future tax year when your overall taxable income might be lower.

Similarly, strategically timing deductible expenses, such as voluntary Pillar 2 contributions or large charitable donations, in high-income years allows you to maximize the tax savings by reducing your taxable income at higher marginal rates.

Property Tax Planning

Owning property in Switzerland provides unique tax optimization opportunities. For instance, mortgage interest payments are fully deductible. However, it is worth noting that amortization (paying down principal) is not deductible.

Consequently, some property owners choose interest-only mortgages (or slow amortization schedules) to maintain ongoing interest deductions. This approach can be particularly advantageous in a low-interest-rate environment.